Victoria: Storytelling is one of the historical transmission channels in Africa, especially in the western part of Nigeria. How far can you access the calamity of its attrition?

Kọ́lá: There is an issue of our haphazard embrace of technology and its power of documentation. The fifties and sixties were a great time to record many of indigenous Nigerian cultural outputs. But even many of the records we made in those days are now either lost to private collectors or totally disappeared. There’s a lot of work to be done, even if it is just to find where these things are, and make them available for others to use.

Victoria: Storytelling appears in almost all of our music, drama and rhythm as Africans. In Yorùbá, we have Rárà (poetry), In Hausa, we have labari (tales), In Isizulu, indaba ezekwayo (tales & myths) How do you think, that we can bring these philosophies back to our school curriculums and our general existence?

Kọ́lá: They still exist in general existence. What we don’t have, like I said earlier, are establishments interested in documenting them and distributing them to the general public. We need more ways to get these indigenous cultural productions to the world. Translation is also one way to do that.

Victoria: What are the best ways to synchronize our historical and cultural nuances with modern values?

Kọ́lá: We are already doing that. A culture survives when its owners know what to keep and what to discard.

Victoria: If you were charged the assignment of impregnating more of African History into our Educational system, what generic elements will you imbibe?

Kọ́lá: I’ll hope that we have a good curriculum on the period of slavery, and the many internicine wars we fought either to keep the system or to expand empire under other names and ambitions.

Victoria: Beyond literary and oratory methods, are there ways we can properly share our community ideas without losing its essence and it’s core relevance?

Kọ́lá: Aren’t we already doing that? Every Yorùbá person you meet anywhere in the world already carries a part of his/her culture, whether they like it or not.

Victoria: Do you succumb to the idea that there are particular traditional beliefs that can be outdated or irrelevant as time goes by? And generations outlive generations?

Kọ́lá: Sure. But most cultures usually don’t die, they mutate into others.

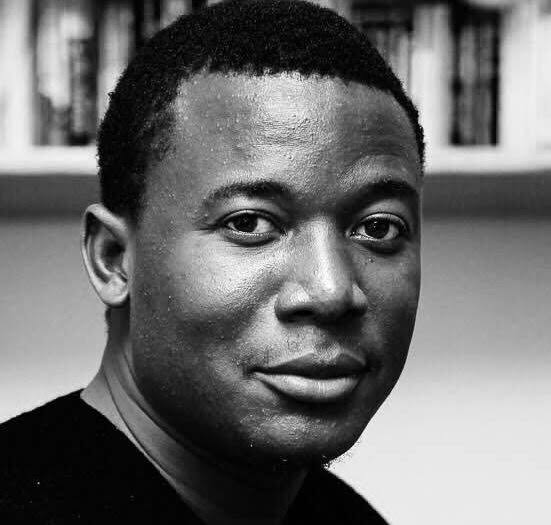

Victoria: You grew up in a family that valued using language and Yorùbá culture to portray life in its essence. Your father is a famous folk poet and he published more than 20 books in Yorùbá, signed various local artists and released various albums that give life to Yorùbá music and poetry in that age. Do you believe that was the rejoining part of your person to the essence of your culture and ancestry?

Kọ́lá: Sorry I didn’t understand this. I assume you want to ask if his work inspired me as a child? Yes, it did.

Victoria: As a Linguist, you have explored the science of language and how we can go beyond seeing language as just messages to understanding the communicative configuration, and how it unites communities. You have through yorubanames.com, reminded us the essence of placing value on our traditions, inscriptions and culture. However, do you feel there is a difference between having a deep sense of language and having just basic communication skills?

Kọ́lá: Yes. Linguistics, which I studied, gave me a unique point of view into how language works. It’s the same way in which learning to become a lawyer makes you more skilled in matters of law than the layperson. But this doesn’t make me a better communicator than others. Communication is something else entirely.

Victoria: You have explored deeply English and Yorùbá and have written poetry in both languages. What differentiates Yorùbá folklores and poetry from any other form, written in any other language, especially within Africa?

Kọ́lá: Yorùbá language is tonal. Many languages are not (English is not). So this makes Yorùbá language poetry totally different to compose and to perform.

Victoria: Beyond churning out words and bringing in familiar conversations and sceneries, do you feel that there’s a link between spirituality and African storytelling? Does one have to transcend from a mental state and thinking to a higher level to properly tell our story?

Kọ́lá: One can infuse spirituality into everything, and one can still approach literature without the spirit, at all. But a good story is a good story.